It’s a chilly Sunday morning and I’m at St. David’s by the Sea in Cocoa Beach. How this good Catholic girl (eight years of school at St. Louise, followed by CCD and Notre Dame) came to be attending an Episcopal church in Florida is a long and winding story, but what matters this morning is that the story begins in Pittsburgh.

Maybe everyone feels this way about their hometown: for my whole life, I have measured the world by Pittsburgh. Rolling hills, windy roads, trees that explode in color in the fall, even winters that stay gray so long that believing in spring becomes an act of faith are just examples of how the world is supposed to be.

That probably sounds ridiculous, considering I moved away after college and probably won’t ever move back, but it’s true. When I got to Albuquerque, the big Catholic families I met felt like home to me. New Mexico’s farolitos glowed just like the luminaria that lined Pittsburgh’s streets every Christmas Eve. Riding the tram to the top of the Sandias felt like riding the incline to the top of Mt. Washington.

Albuquerque surprised me and stretched me, but it was the ways it felt like Pittsburgh that turned it into home.

When I say Pittsburgh,

mostly I mean aunts and uncles and more cousins than I could keep track of. I mean directions that include lines like “Turn right where the Heigh Ho used to be,” or the time my husband asked, at the bottom of Marvle Valley Drive (and once again, spell check, I am NOT misspelling Marvle), “Should I turn right or left?” and I said, truthfully, “It doesn’t matter.” I mean kissing my high school boyfriend in the woods at Lions Park and balancing on a lightning-struck tree at the end of the circle. (We never said “cul de sac” back then.)

When I say Pittsburgh I mean neighborhood block party parades and carnivals to raise money for muscular dystrophy and roller skating parties and holding hands at the mall. I mean putting empty bread bags on your feet before you put your boots on and sled-riding until you couldn’t feel your hands. I mean playing pinochle, and Parchisi, and Life.

When I say Pittsburgh I mean anise cookies at Christmas, nuts for cracking in a bowl on the hearth, and the way bare branches etched the sunset into panels of stained glass in the backyard. I mean the cinders in my knee from falling on my way to the bus stop and Mrs. Wuske bandaging me up before the bus came.

I mean sitting outside on long summer nights with Billy Wuske and Roger Oldaker, calling up truckers on Billy’s CB. And I mean the football players gathered at John McMillan UP church for Billy’s funeral, when we were all way too young to die.

When I say Pittsburgh,

I mean home.

That might be an example of a literary device called metonymy, but I’m not sure. For all my years as an English teacher, I avoided that term. It sounds simple enough on the surface: “a literary device in which one representative term stands in for something else. For instance, ‘the Crown’ is a metonymy for monarchy rule.”

I could give kids that definition, but once they started throwing out examples and questions, I’d lose my confidence. So maybe Pittsburgh is a metonymy for home. Or maybe it’s just an ache, somewhere between here and Route 79.

Sunday morning at St. David’s by the Sea

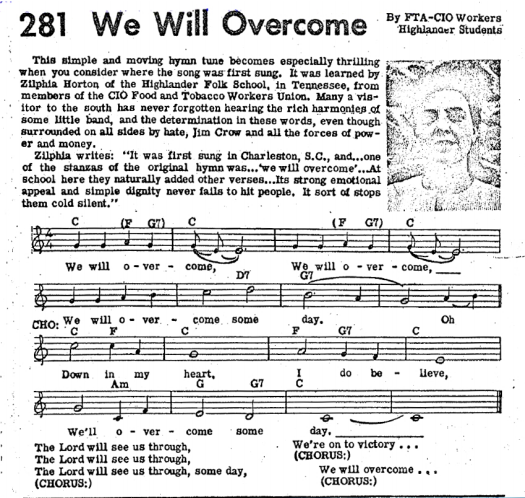

an Episcopal priest reads the words of the Mourner’s Kaddish, ending each invocation with an invitation to the congregation to say “Amen.”

Not surprisingly, I don’t know this prayer. I am expecting sad words, pleas for help, psalm-like cries for deliverance. What I hear instead are words of life, of praise. Words like these:

Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored,

adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He,

beyond all the blessings and hymns, praises and consolations that

are ever spoken in the world…

I’m stunned. I remember the little white candles my father-in-law kept in the pantry to light once a year, and I see, I think, how these words, recited over and over, might call a grieving person back to joy.

Later in the service, the pastor points to the glass windows surrounding the sanctuary. He reminds the congregation that there is a code word. If we hear the word, he tells us, we should run to one of five rooms in the building that have solid walls and locks on the doors. He points like a flight attendant reviewing a safety card to the two doors behind the altar.

He doesn’t say that we will probably hear the shooting before the code word, or that it might not matter that we have a plan.

I am hearing blessed and praised, glorified and exalted…

When I say Pittsburgh,

I never meant Las Vegas, or Orlando, or Blacksburg, or Charleston, or Sandy Hook or Sutherland Springs. Those words, I think, have become metonymies.

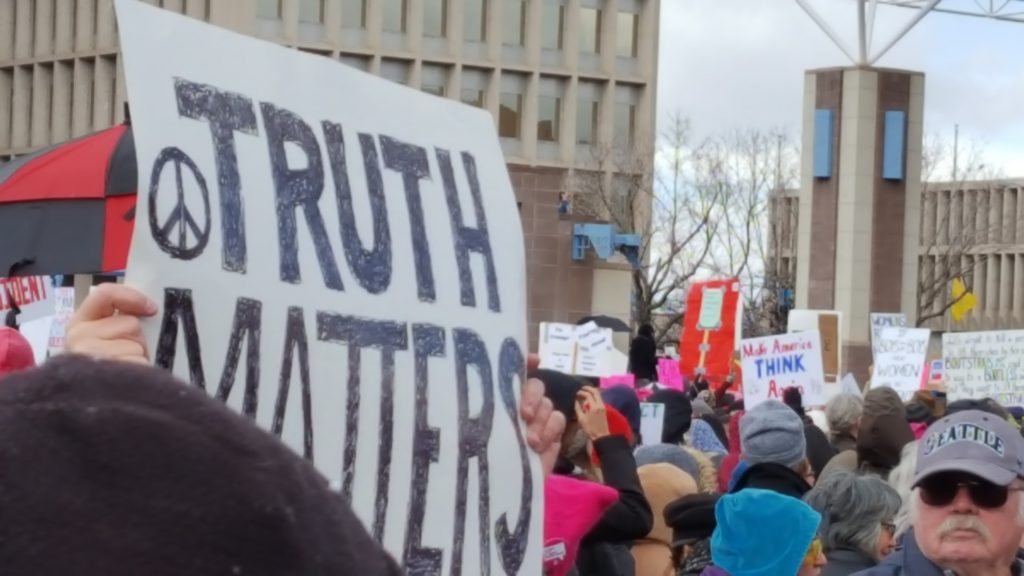

What matters this morning is that the story started in Pittsburgh and that, one more time, people are mourning.

In Washington, the man who calls himself a nationalist (which I believe just might be a metonymy) is tweeting that the “Media is the Enemy of the People.”

In Pittsburgh, Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers of the Tree of Life Synagogue reports that he has lived with anti-semitism for his whole life, but this is different. The hate, he says, is getting worse.

Then the Rabbi said, “I will not let hate close down my building.”

To which we say: Amen.