Yesterday afternoon while the wind blew and the pollen tried to kill me, I was learning to count.

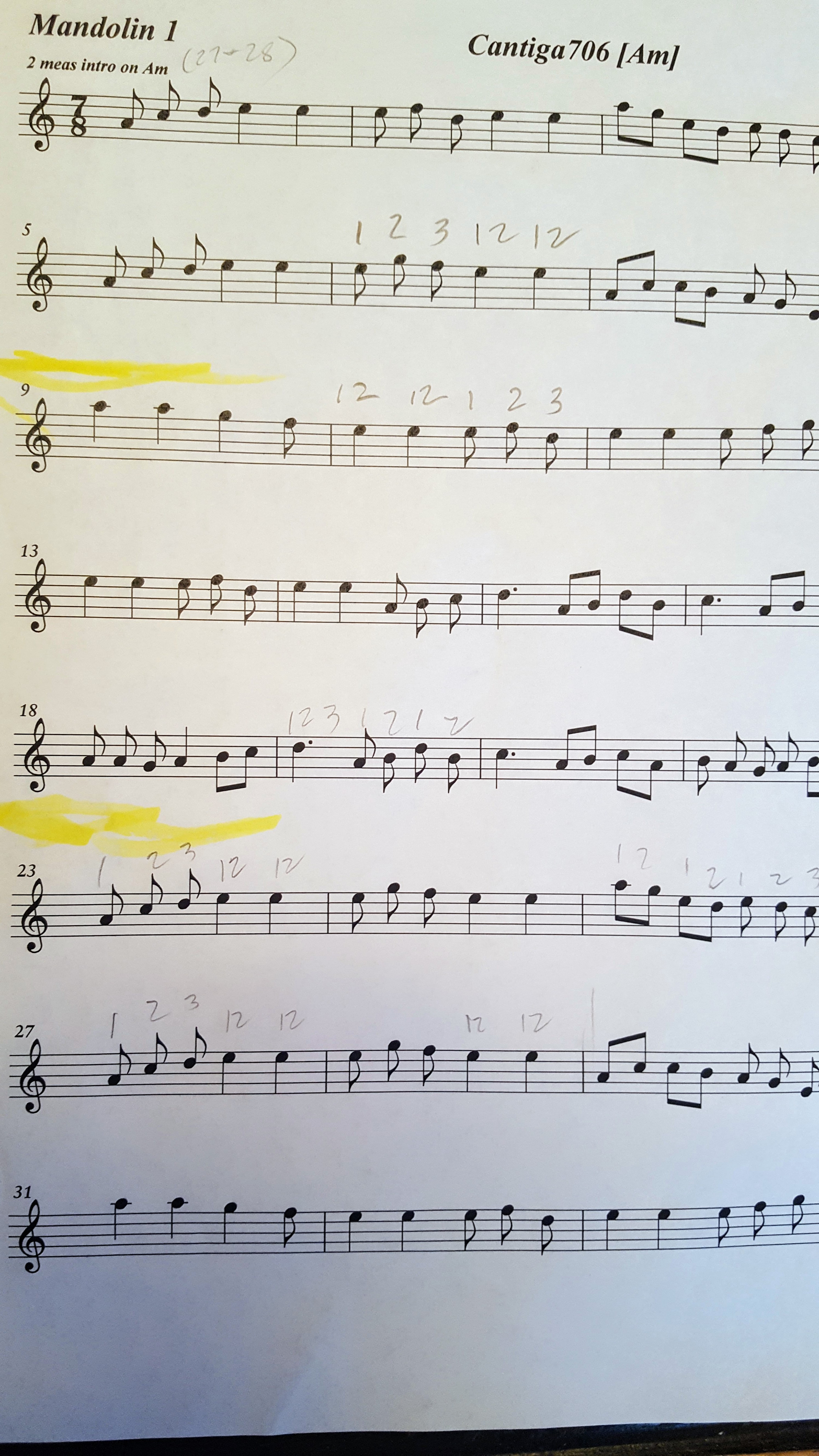

The question at hand was this: Is it 1-2-1-2-1-2-3 or 1-2-3-1-2-1-2? For a few minutes as the numbers were flying, I could feel the panic room shields locking into place around my brain.

Does this happen to you?

Sometimes when too much information comes at me too quickly my brain just stops. Picture a little kid covering her ears and singing “lala-lala-lalala” when she knows you are about to tell her there is no Easter Bunny.* Or worse, if you’re an Apple user, picture that spinning color wheel of death.

Nothing good ever happens after the colors start spinning.

So yesterday afternoon at mandolin orchestra practice when I asked, “How are you counting those two measures in the introduction?” and Ken started calling out numbers, I felt my inner la la girl reach her hands toward my ears.

I don’t know if this shut-down feature has gotten worse as I’ve gotten older, or if I’ve just become more aware of it. All these years of encouraging students to reflect on their learning after every project might be rubbing off on me. (Where was it hard? Where did you get stuck? How did you move past that point? What are you most proud of?)

I had a similar shut-down moment a few weeks ago. I was walking through a model home with a realtor who wouldn’t leave my side. She had a really loud voice, and she wouldn’t stop talking. In fifteen minutes, I learned details about her life story that I couldn’t tell you about some of my closest friends.

I finally had to interrupt her in mid-sentence and run out the door, leaving Fred to mop up for my abrupt departure.

So Sunday afternoon

after Ken said 1-2-1-2-1-2-3 and 1-2-3-1-2-1-2 and Michael said 1-2-3-4-5-6-7 (and I snapped “That’s not going to be helpful at all,” at him), I thought it was all over. I was about to resign myself to being lost on the intro and hoping I could catch up a few measures in.

And then something funny happened. I looked at measure 48 and saw it–three eighth notes followed by two quarter notes: 1-2-3-1-2-1-2. Then measure 49 came into focus. Even measure 51: half note, eighth rest, eighth note, eighth note (1-2-1-2-1-2-3) started making perfect sense.

Maybe you have been confidently playing music in 7/8 time for years, and you’re wondering why this was hard for me. Or maybe you don’t read music at all and you have no idea what I’m talking about. (Sorry about that!)

Or maybe you are neither of those people and you are just trying to figure out what the big deal is about a 54 year-old finally learning to count.

I’m trying to figure that out, too.

But the thing is, it was a big deal. It’s not just about learning to count in a 7/8 time signature. With as much music as I’ve played and sang in my life, it’s more remarkable that I’ve never learned that before.

What excites me is that, when my familiar shut-down moment appeared, my old brain did something new. It wedged its foot in the elevator doors before they slammed shut. To quote my uncle, that’s big potatoes.

I’ve always been able to empathize with students who have test anxiety. I’ve always assumed they felt just like I feel when my la la girl starts singing. Now, though, I can do more than empathize. I can assure them that their brain can do something different.

But how?

I can’t claim to know that what happened Sunday is repeatable, but I can tell you what I noticed.

First, I gave myself permission to fail. I was resigned to my confusion. I let go of any pressure to succeed, any pretense that I knew what I was doing, and any disappointment over not already knowing how to do this.

Second, I was persistent (some in the Albuquerque Mandolin Orchestra might, if they weren’t such kind people, say annoying) in asking for what I needed. I kept saying things like, “Could you do that again more slowly?” or “Could you tell me how you’d count measure nineteen?”

Third, I was grounded. I’ve been making some big decisions lately (more about that in a future essay), and those decisions have left me feeling clear and solid. Years ago the city of Albuquerque brought goats (a flock? a herd? a scrabble? a gabble?) into the bosque to eat the salt cedars.

I feel like the bosque must have felt the next day: the goats have eaten away the underbrush and the path is clear.

In The Book of Awakening,

Mark Nepo writes, “the way to stay in the presence of that divine reality which informs everything is to be willing to change.” A dear friend gave me this book, and pointed out the section called “The Gift of Shedding.” Shed what? “Whatever has ceased to function within us…whatever we are carrying that is no longer alive” (104).

I don’t mean to argue that loving yourself is some pat cure for test anxiety, but I do know that learning to count didn’t happen while the weeds were wrapped around my ankles.

One more thing about learning to count. I thought about telling you this happened in a dream so you wouldn’t think I’m crazy, but that feels like cheating. Sunday afternoon before I went to mandolin practice I was leaning on my kitchen counter, just sort of lost in thought.

All of a sudden I had this weird image: my chest opened up like one of those shoe box dioramas little kids make, and a whole menagerie of colorful animals came trotting out of my chest into the world.

I don’t know quite what to make of that vision (brain tumor?), but I thought it might be relevant.

I’ll leave you with that thought while I go play a little mandolin. The Albuquerque Mandolin Orchestra is opening for Nell Robinson and Jim Nunally in a house concert this Friday evening, and while learning to count Cantiga 706 in A minor is great, it’s not the same thing as being able to play it.

(* That little girl is singing la la in a count of 1-2-1-2-1-2-3. See what I did there?)

+++++++++++++++++++