At first I wasn’t sure it was possible to prune a peace lily; I thought we would just have to keep going on together as we had been. Several times a day she would beg for water, and I would mumble, “Already?”

Then, her leaves would droop lower and lower until I complied, tipping cool water from a pitcher into the ground below those elephantine sails. In October when my sister came to visit, I warned her. “The peace lily will probably wake you up in the middle of the night to ask for a drink of water.”

Let me be clear: I love the peace lily.

She came as a gift from my colleagues when my mother died in 2015. At that point, she was already a huge plant; I felt like I was hacking through a rain forest as I carried her from my desk to my car.

I got her home and rearranged some furniture to give her a home in the guest room, where the odds of her survival were slim. I’ve been know to kill ficus and spider plants; surely this exotic creature was at risk in my care. We soon fell into an imperfect rhythm. I’d water her faithfully every Sunday with the other plants, and then forget about her until some stray errand took me into the guest room where I’d find the tips of her extravagant leaves dragging on the floor.

Eventually I adjusted my routine. I checked on her daily, but every time I went in, I found her drooping and calling out for more water. Things went on like this for a long time. When I realized my other relationships were beginning to suffer, I knew I was going to have to learn how to prune a peace lily.

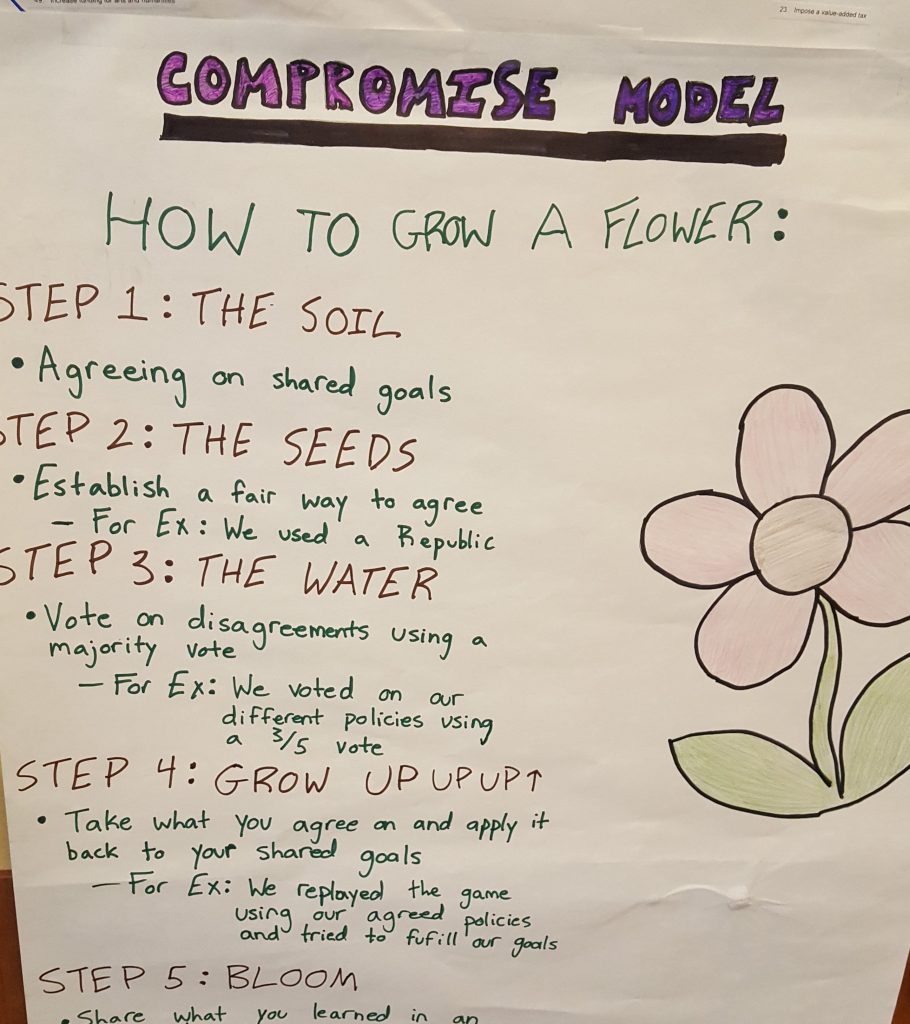

Here’s how I did it.

Step One: Acknowledge your discontent

I tried to change other things: I thought about working out more, eating better, drinking a little less wine. None of them worked. (That might have been because I only thought about doing those things, but I digress.)

I had to say it out loud. The needs of my beloved peace lily were taking over my life. Eventually, I had to ask myself the big question: Is this relationship keeping you from being who you are meant to be?

When I finalIy recognized that my dissatisfaction was rooted in the same pot as my peace lily, I called a wise friend. “I’m not surprised,” she said, surprising me. “You’ve been making this change for a long time; you just didn’t know its name.”

Step Two: Make the Easy Cuts First

Armed with my kitchen scissors, I entered the jungle. I didn’t know how my peace lily would react to my pruning. I started with the leaves that had gone brown around the edges, following their stems deep into the heart of the pot. A snip here, a snip there. Soon my hands were overflowing with enough giant fronds to make a banana tree, but I wasn’t looking to start anything new here.

I carried the fronds to the trash can outside and dumped them in. “There,” I thought. “I’ve done it. I can go on.” Now I just had to wait to see if she survived.

Step Three: Re-evaluate the situation

She’s still thirsty, unmoved by my pruning. Our co-dependent droop-response cycle slows down, but the same old rhythm pulses. I cut back from watering every day to watering every other day, but it’s not enough.

“It’s not you, it’s me,” I tell her. Having tasted freedom from her needs, I’m hungry for more.

Step four: Be bold; cut deeply

This time when I enter with the kitchen shears she trembles a bit, tries to pretend it’s just a breeze. I’m going to take them all this time, I tell her. Every leaf that’s bigger than my face must go. I cut until my hands are full then walk, looking like a palm tree, outside to the trash.

My dog, confused by my arboreal transformation or the peace lily’s perambulation, barks at me. Undeterred, I do it again. And then again.

When I’m finished, I’m surprised by how deep I was willing to go.

Step Five: The Reveal

I wasn’t sure for a few days if she was going to make it. She didn’t droop, but since drooping had been our main form of communication, I didn’t know how to interpret her silence.

The next morning I walked in to see if she needed anything. I opened the blinds to give her some sun and saw it. New, bright green leaves, younger than the whole world, were pulsing up from the base of the stems.

I could have sworn she was laughing.

And that’s how you prune a peace lily.

It turns out that pruning a peace lily is not that unlike making any other big change. Something nudges you, and then that nudge turns into a whisper. You ignore it for a while, but if it’s a real call, it keeps buzzing in your ear. You can’t swat it away.

It just keeps getting louder and more insistent until you figure out what the heck it’s been trying to tell you all this time. Rilke says, “Everything is gestation and then bringing forth.” It turns out that if you till the soil, plants are inevitably going to grow.

Rilke also says, “This above all–ask yourself in the stillest hour of your night: must I write? …if you may meet this earnest question with a strong and simple ‘I must,’ then build your life according to this necessity; your life even into its most indifferent and slightest hour must be a sign of this urge and a testimony to it.”

That passage has been haunting me since I first read it as a freshman in college, when I was still as green and unfurled as those new leaves on the peace lily.

It has taken me more than thirty years to say I must out loud, to make the deep cuts and hack off the old, beloved growth. In less than two weeks I’ll be wrapping up this phase of my life as a high school teacher. It feels heartbreaking and wonderful; terrifying and invigorating at the same time.

Oh–and one more thought about that peace lily. Just last week it burst into bloom.

As always, if you enjoyed this post, feel free to share it with your friends and tell them about LiveLoveLeave.

![Note from the seniors reading "We [heart] you Ms. O'Shea"](https://liveloveleave.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/20180504_100844-2000x1200.jpg)