I never met Ursula Le Guin, but we go way back. I was in college when I read The Left Hand of Darkness for the first time. I was fifty-one or fifty-two the last time I read it. In all the readings in between, it’s never failed to teach me something.

If you haven’t read the book, or if it’s been a while, here’s the gist of Le Guin’s story. Genly Ai, an envoy for the Ekumen (think intergalactic UN), travels to the planet Winter. Winter is a cold place where the humans are not exclusively male or female. Sometimes, when they enter “kemmer,” their sexually active phase, they develop male genitalia. Other times, they become female. In other words, the same character that gives birth to one child might father another.

Le Guin explains, “The fact that everyone between seventeen and thirty-five or so is liable to be…’tied down to childbearing,’ implies that no one is quite so thoroughly ‘tied down’ here as women, elsewhere, are likely to be–psychologically or physically.”

Genly’s mission is to invite the people of Winter to join the Ekumen. He isn’t there to coerce or cajole, but simply to enter into relationship. Estraven, sort of “prime minister” to the King of Karhide, is the sole character on the planet who believes the truth about Genly and responds to it with an open heart. Genly, unfortunately, is too ensnared by his biases for most of the book to receive that friendship.

I don’t want to spoil the story for you. Instead, I’ll share a few things I’ve learned through my thirty-plus year paper friendship with Ursula Le Guin.

In My Twenties, Ursula Le Guin Taught Me that Having Gay Friends Didn’t Mean I Wasn’t Homophobic

My twenties started in 1984.

I remember one time when I was home visiting my parents. I was in the backseat, and Rush Limbaugh was on the radio. “Why do you hate him so much?” my father had asked.

“Because I spend my days teaching kids that critical thinking matters. I tell them that being loud and sarcastic isn’t the same as making a good argument,” I replied. (Probably more snarkily than I might have now. And I wouldn’t have used the word “snark” back then.)

We probably didn’t talk much more about Rush Limbaugh on that trip. And it would be many more years before my mother would tell me that I “had the wrong opinion about everything.”

Besides, that’s not my point, and I’m cheating. That conversation belongs in my thirties, after I’d started teaching. But because listening to my mother’s favorite radio talk show wasn’t conducive to having a good visit, my dad changed the station.

Babe the Sports Animal came on next. I don’t know if Babe the Sports Animal was a Pittsburgh thing or if other people have heard of this program. I’d give you a link, but the quick search I just did led me to a bunch of sites that pissed me off.

Anyway, we were driving down McMurray Road listening to Babe the Sports Animal talk about the Steelers. After a little while, my dad revealed that Babe was a woman, but I couldn’t believe it. I had just spent twenty minutes or so thinking I was listening to a man. Try as I might, I couldn’t put that voice back into a woman’s body.

I yanked that story into the wrong decade because that’s how Genly Ai feels on the planet Winter. He says, “Though I had been nearly two years on Winter I was still far from being able to see the people of the planet through their own eyes. I tried to, but my efforts took the form of self-consciously seeing a Gethenian first as a man, then as a woman, forcing him into those categories so irrelevant to his nature and so essential to my own.”

Much of Genly’s work on the planet, he’ll learn slowly, is not to change the Gethenians. Instead, he realizes, he has been sent alone so that he can be changed.

As Genly’s friendship with Estraven deepens, (at one sexually charged point Genly notes that it “might as well be called, now as later, love”), Genly finally learns to accept Estraven as he is. At the moment of his revelation Le Guin writes, “And I saw then again, and for good, what I had always been afraid to see and had pretended not to see in him: that he was a woman as well as a man.”

Something cracked open in me when I read this book in my twenties. I realized that I’d been holding on tightly to the idea of the “other.” A few friends had come out to me in high school, and I was pleased with myself for my “acceptance.”

Le Guin taught me that my “acceptance” rested in a firmly lodged sense of difference. It was an acceptance that created a chasm, rather than bridging one.

At one point in the novel Le Guin writes that on the planet Winter, “One is respected and judged only as a human being.” Twenty year old me took that as a call to action, and it made me a better person.

In My Thirties Ursula Le Guin Taught Me That Being A Feminist Didn’t Mean I Wasn’t Biased Against Women

My thirties started in 1994.

Remember the story about Babe the Sports Animal I just told you? I don’t know if it was Babe’s particularly deep voice or my particularly deep bias that made me certain that The Sports Animal was a man.

I do know that every year (until my very most recent reading), when I read Chapter 7, “The Question of Sex: from field notes of Ong Tot Oppong, Investigator, of the first Ekumencal landing party on Gethen…” I assumed the investigator was a man.

EVERY SINGLE TIME.

Le Guin knew I was reacting that way. Why else end the chapter with this sentence: “I am a peaceful woman of Chiffewar…”?

Early on, Le Guin received criticism for some of the choices she made in the book. Despite her groundbreaking work with gender, she chose to use masculine pronouns throughout. Her descriptions of the “male” and “female” characteristics of the people of Winter stay largely true to stereotype. The descriptions of the relationships between the characters are largely heteronormative. (I’m cheating again. I wouldn’t have had that word available to use in my thirties.)

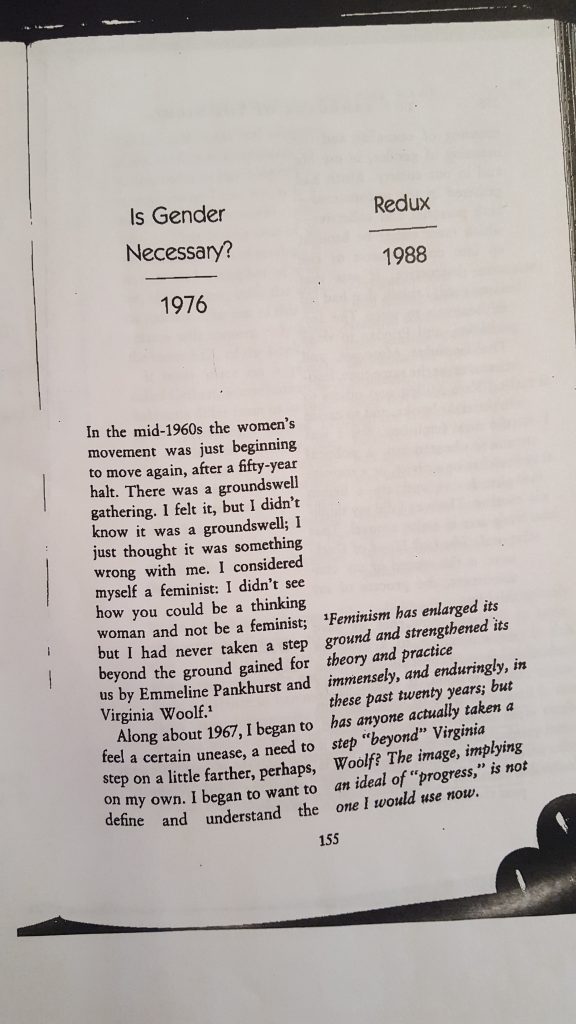

In a 1976 essay called “Is Gender Necessary,” Le Guin defended her choices, sometimes defensively. She wrote, “The fact is that the real subject of the book is not feminism or sex or gender or anything of the sort; as far as I can see, it is a book about betrayal and fidelity.”

But then she did something remarkable. In 1988 she wrote “Redux,” in which she responded paragraph by paragraph to her former self. “This is bluster,” she says of her earlier statement. “I was feeling defensive.”

It wasn’t enough that Le Guin wrote a novel that helped me to see my own biases. Then she wrote an essay that taught me how to forgive myself for them.

In My Forties Ursula Le Guin Taught Me that “Progress is Less Important than Presence”

My forties started in 2004.

These were the years when I traveled with students to spend a week practicing Buddhism at the Bodhi Manda Zen Center in the Jemez Mountains northwest of Albuquerque.

I sat zazen, swept sidewalks, and filled birdfeeders. Ursula Le Guin said, “Compare the torrent and the glacier. They both get where they are going.”

In My Fifties Ursula Le Guin Taught Me That the Fact That I’d Loved Her Book for Decades Didn’t Mean I Knew Anything About What it Means to be a Transgender Person

My fifties started in 2014.

As the country moved toward the 2015 Supreme Court decision on gay marriage, I wondered if the book had done all the work I needed it to do. It seemed like it might be time to stop teaching it.

Then I read it again after I’d learned a little about the transgender community. I finally realized it had never been a book about overcoming homophobia. All those years I was assuming Genly was uncomfortable with his feelings for Estraven when Estraven was a man, but the text had never said that. That was my bias speaking again.

At the end of the novel when Genly is reunited with beings like himself, he is uncomfortable. “But they all looked strange to me, men and women…Their voices sounded strange: too deep, too shrill…”

He remains uneasy until he is again with a Gethenian. The young physician has “a human face.” It is “not a man’s face and not a woman’s.” Genly can relax at last, at home with a human being.

In My Sixties and Beyond, I Don’t Know What Ursula Le Guin Will Teach me.

Ursula Le Guin died last Monday at age 88.

My sixties will start, with any luck, in 2024. Tomorrow I’ll turn fifty-four. I’ve bumped up against the edge of where this story can take me for now.

I realized, though, that despite having read Left Hand of Darkness ten or twenty times, I haven’t read much of Ursula Le Guin’s other work. I always meant to. In that way, Le Guin lives on for me.

If you’ve read The Left Hand of Darkness, you know that I’ve left whole themes, maybe even the most important ones, unmentioned. The book, to me, will always be mostly a love story. But it’s also a book that questions our ideas of power, masculinity, and government.

In fact, I feel like I should leave you with one final quote. After his beloved friend skied off to meet his fate, Genly “wondered, not for the first time, what patriotism is, what the love of country truly consists of… and how so real a love can become, too often, so foolish and vile a bigotry.”

Rest in peace, Ms. Le Guin. I’m confident we’ve all still got a lot to learn.

++++++++++++++++++++++++